Yearning to Breathe Free: The Story Behind the Statue of Liberty

Posted by Pete on Oct 28th 2021

Some say statues aren’t political: they’re there to preserve history, not make it. How about we test that theory against the most famous statue in the world?

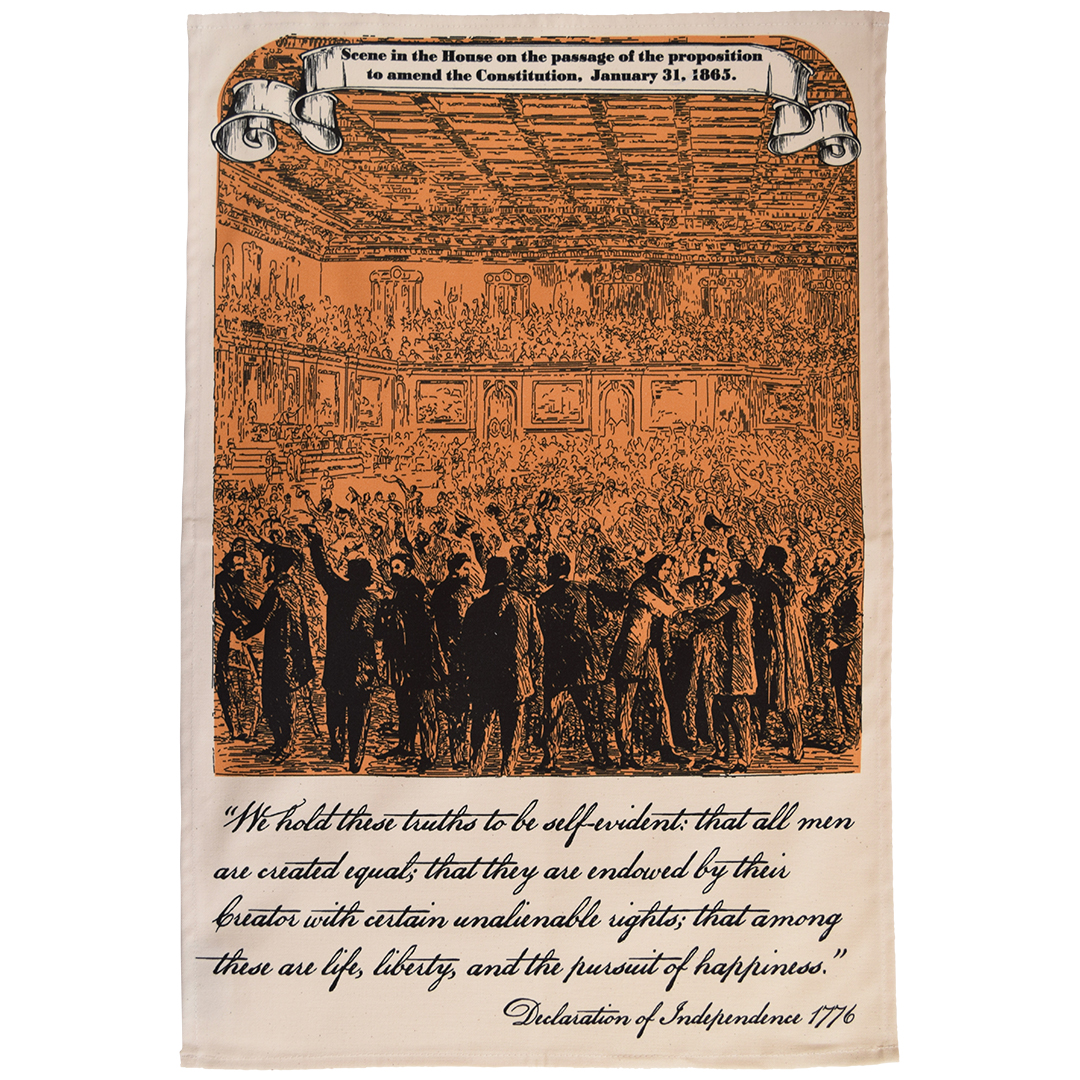

The late 1860s and early 1870s were a brief high point for black liberation in the US.

The Confederacy had just been smashed and the Constitution was being remade to entrench abolition with the Reconstruction Amendments.

It was against this backdrop that two Frenchmen, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and Édouard René de Laboulaye, came up with the idea for a Statue of Liberty.

The Reconstruction Amendments aimed to reconstruct the South after the Civil War and to reinforce the rights of African Americans.

View our Reconstruction Amendments tea towel

Laboulaye was President of the French Anti-Slavery Society. The statue, as well as being a general commemoration of the historical Franco-American alliance, was intended to mark the more recent defeat of slavery in America.

But by the 1860s, there was already a history of ‘statue wars’ over slavery in the US.

When the sculptor, Thomas Crawford, designed the Statue of Freedom for the top of the Capitol in the early 1850s, he originally planned for the figure of Liberty to wear a pileus.

A pileus was the conical hat given to emancipated slaves in ancient Rome, so, given this abolitionist association, it was vetoed by then Secretary of War (and future Confederate President) Jefferson Davis. Liberty would wear a helmet, instead.

But when the French got to work on their statue, the Confederacy was dead and buried. The project had full support from leading Americans, not least President Ulysses S. Grant.

The head of the Statue of Liberty at the Paris Exposition, 1878.

That said, white supremacy wouldn’t be on the back foot for long. By the 1880s, when the Statue was finished, the old slave aristocracy was re-established in the national elite.

On top of this, the French designers were hardly radicals.

Though they were abolitionists, Laboulaye and Bartholdi were opposed to their own country’s revolutionary tradition.

Their figure of Liberty was to be a moderate version, not a rebellious one.

As such, she wore no pileus. Fearful of antagonising the newly-rehabilitated Southern elite, earlier drafts of Liberty holding a broken chain in her hands were rejected. Instead, the broken chain would be placed subtly under her foot, mostly covered by the robe.

Indeed, the original title of the statue was La Liberté éclairant le monde (‘Liberty Enlightening the World’). The designers meant it as a symbol of wisdom, not revolution.

But, as it happened, Americans didn’t really care about what Bartholdi and Laboulaye thought the statue was supposed to symbolise: its meaning was in the hands of the American people.

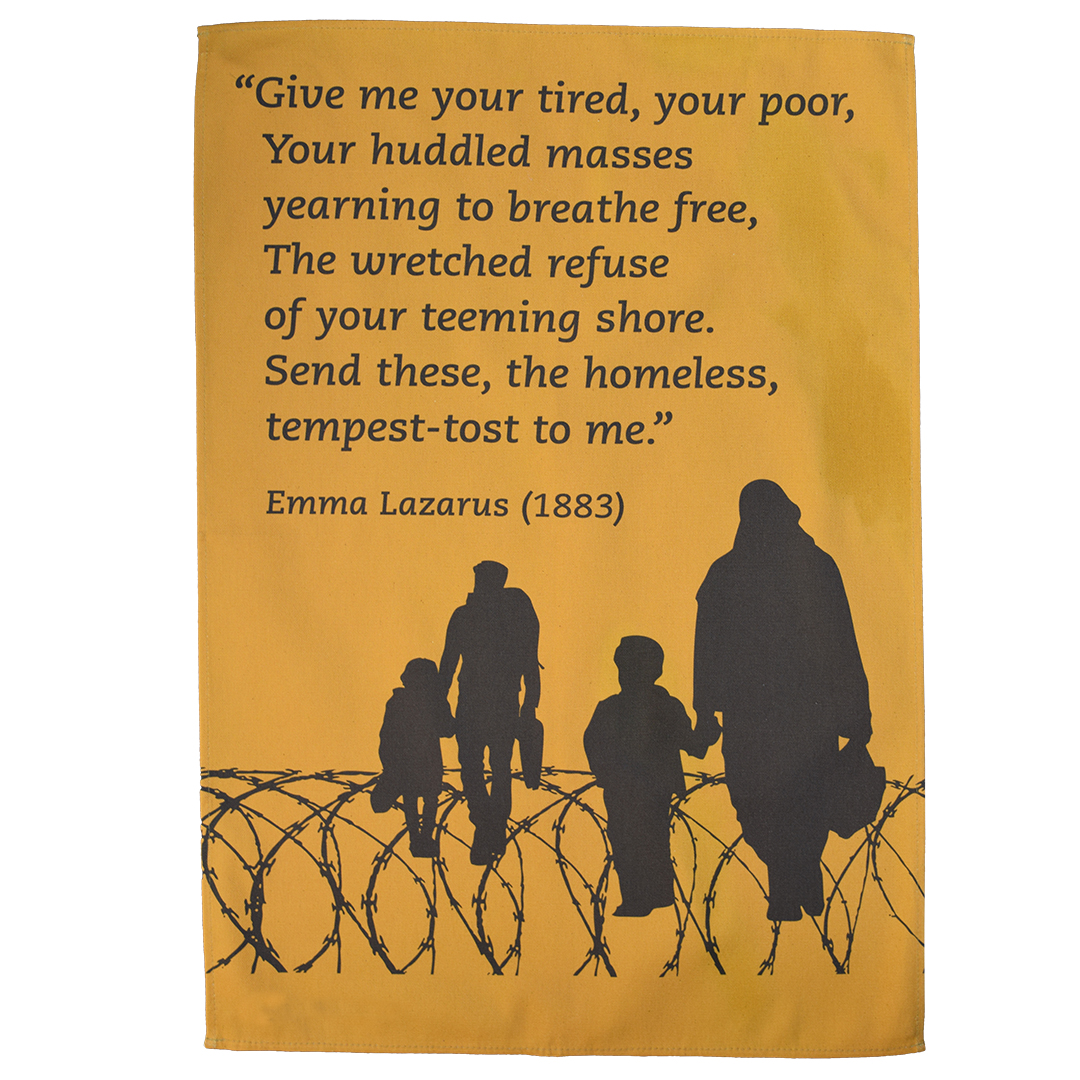

These lines come from Emma Lazarus's poem 'The New Colossus', written in 1883 to raise money for the statue's pedestal.

Emma Lazarus, who had been working with Jewish refugees from the pogroms in Eastern Europe, decided to turn it into a symbol of asylum for immigrants and exiles.

Others just took the Statue as a tribute to American freedom in general, and celebrated it – or questioned it – accordingly.

From the very beginning, there were those who asked ‘what freedom?’

At a time when racist Jim Crow laws were taking root in the South, African-Americans challenged the idea of a Statue of Liberty in the first place.

The Cleveland Gazette wrote,

‘“Liberty enlightening the world,” indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders. Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the “liberty” of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man to earn a respectable living for himself and family without being ku-kluxed.’

Frederick Douglass had asked in 1852, ‘what to the slave is the Fourth of July?’ The question now was, amid segregation and disenfranchisement, what to the African American is the Statue of Liberty?

So it seems, even from its conception, the world’s most famous statue was as political as it gets.

Its design and construction, and then its (debated) presence in New York, were not the preservation of history – they were history, contentious, rowdy, and full of politics.

Key dates:

- 1870: Bartholdi and Laboulaye come up with the idea for a Franco-American Statue of Liberty

- June 1871: Bartholdi visits the US to raise support

- September 1875: The project is formally announced

- 3 March 1877: On his last full day in office, President Grant signs a Joint Resolution empowering the President to accept the Statue from France once complete

- 1880: Gustave Eiffel is brought onto the construction project

- 4 July 1884: The completed Statue is presented to the US Ambassador in Paris, while work continues on the pedestal in New York Harbour

- 17 June 1885: The French steamer, Isère, arrives in New York Harbour carrying the disassembled Statue

- 28 October 1886: The Statue of Liberty is formally dedicated in New York Harbour after a massive parade through the city