Frances Harper and the Poetry of Freedom

Posted by Pete on Sep 24th 2020

Frances Harper, the unofficial poet laureate of abolition, was born today in 1825.

In a lowly plain, or a lofty hill;

Make it among earth’s humblest graves,

But not in a land where men are slaves.

Every revolution needs its art.

The working-class movement in 19 th century England had the poetry of Shelley and the textiles of William Morris, and the Mexican Revolution had the painting of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

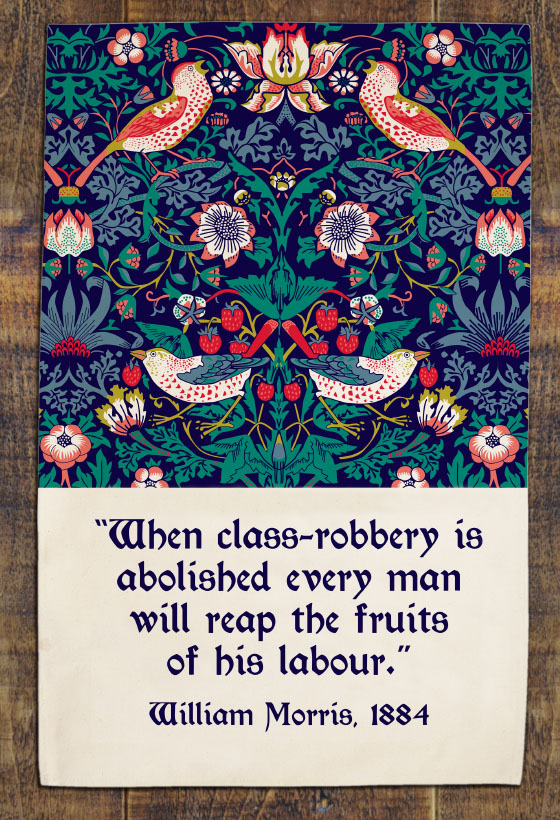

In the people’s movement against slavery in the US, it was the poetry of Frances Harper (1825-1911) which helped to give the grim struggle a sense of wonder.

Born free in Maryland, a slave state, Frances Harper was a talented young black woman in a hostile world.

She got an education in Baltimore, at the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth (founded by her uncle, who was himself an abolitionist cleric), while also working as a seamstress and nursemaid when she was still just a child.

Frances soon found work in the North as a teacher, but her real passion was writing.

In 1859, she became the first black woman in US history to have a short story published.

She was also a poet, publishing her first collection of poetry, Forest Leaves, in 1845.

In 1853, Frances had joined the American Anti-Slavery Society. She did a two-year tour of Maine, giving public lectures against slavery.

And there was no wall between her political activism and her writing.

Plenty of Frances’ poems and stories were critical of white supremacy in the United States.

Her poem ‘The Slave Mother’ recounted the brutal destruction of black families by the institution of slavery, and ‘To the Cleveland Union Savers’ took aim at the Fugitive Slave Law.

What’s more, poetry was not an alternative to other forms of radical political action for Frances Harper.

As well as her lectures for the Anti-Slavery Society, she helped out on the Underground Railroad.

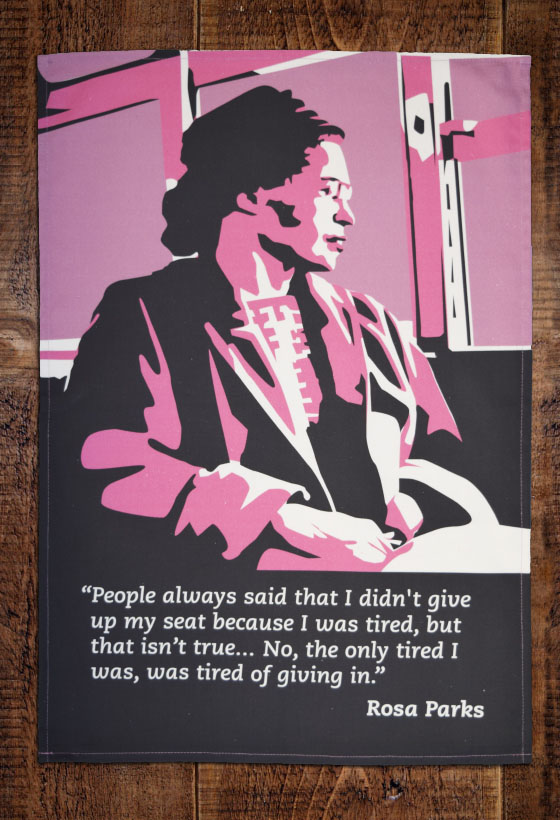

In 1858, a century before Rosa Parks, Frances refused to give up her seat in the white section of a segregated trolley car in Philadelphia.

In 1859, she mourned John Brown and his comrades after their heroic raid on Harpers Ferry:

After the defeat of the Confederacy, Frances went south to provide teaching services for the Freedmen’s Bureau.

She also became a major voice in the women’s suffrage movement, protesting the increasing racism of its white leaders – especially the opposition of Susan B. Anthony and others to the enfranchisement of black men.

Against the racism which was corrupting the established suffrage movement, Frances set up the National Association of Colored Women with Mary Church Terell, serving as its VP from 1897.

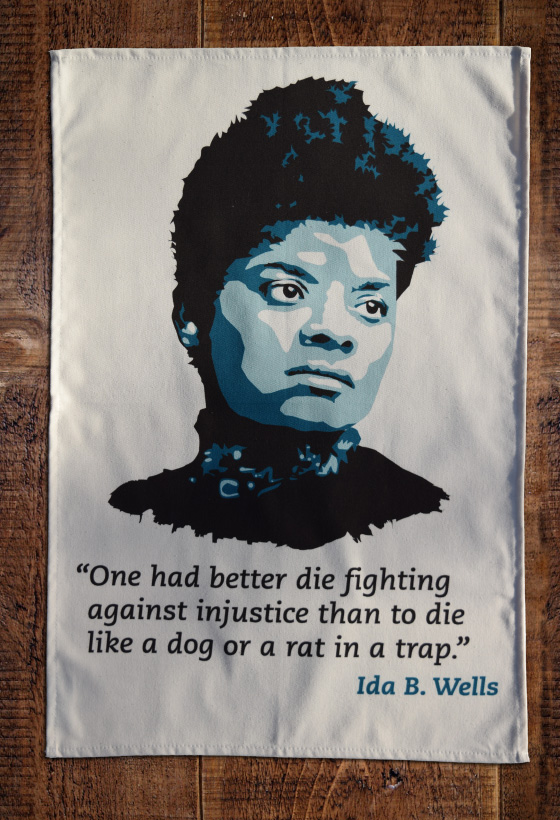

In her old age, Frances was increasingly seen as a mentor by radical, young black women in the US like Ida B. Wells.

Frances Harper died in 1911 after almost a century of battling the structures of white supremacy and patriarchy in the United States.

Every revolutionary movement needs its own art to give it soul, as well as strength, and the radicalism of America’s 19 th century owes a large part of its soul to Frances – poet, author, freedom fighter.